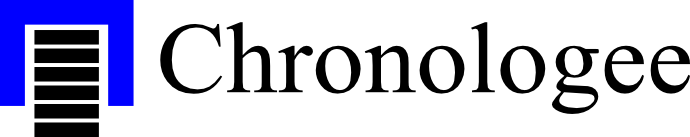

“Well, the people, I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?” Those were the words of Jonas Edward Salk in a 1955 interview after Edward R. Murrow asked who owned the patent for the newly developed polio vaccine.

Jonas Edward Salk became a national hero on April 12, 1955, when he announced the success of his inactivated polio vaccine (IPV). According to the World Health Organization, this development rapidly reduced polio cases in the United States and globally. After its announcement, the vaccine was also licensed that same day.

Polio, When Did It Start?

While it’s believed that polio began far back in ancient Egyptian era between 1580-1350 BCE, it wasn’t until 1789, when British Physician Dr. Michael Underwood gave the first recorded clinical description of the condition, describing it as a “debility of the lower extremities.” And by 1840, German Physician, Dr. Jakob von Heine carried out the first thorough study of polio and proposed that the illness could be contagious.

Then came 1894, the year the United States recorded its first significant polio outbreak. However, it was not until 1908 that a breakthrough discovery was made. Austrian physicians Karl Landsteiner and Erwin Popper isolated the poliovirus and confirmed that the disease is caused by a virus. By the early 20th century, polio outbreaks became more common and more serious in developed countries. This happened partly because better sanitation meant babies weren’t exposed to the virus early on, when their mother’s antibodies could still protect them. Instead, they caught it later in childhood, which made the illness much more dangerous.

It was during this time, on October 28, 1914 that Jonas Salk was born, in New York City to a Russian-Jewish immigrants.

The Severity of The Epidemic

Two years after his birth, the United States began experiencing its worst polio epidemic in the country’s history. His parents, both factory workers, were deeply worried about their little boy.

In 1916 alone, New York City recorded the highest polio hits with about 9,000 children affected, and killing 2,343 of them. Cardboard notices reading “INFANTILE PARALYSIS” were nailed or placed on the doors of homes and apartment buildings where a case of the disease was identified. They warned people not to enter or leave the premises, as ordered by the Board of Health. Thousands, particularly those who could afford to, fled the city, and those who stayed were forced to keep their children indoors.

Jonas Salk’s Education

He attenuated Townsend Harris High School, a public school for intellectually gifted students that crammed a four-year curriculum into three years, and finished at age 15. He first thought about becoming a lawyer, but after taking biology classes in college (at the City College of New York), he chose to study medicine instead. Over time, Jonas Salk grew interested in viruses — tiny organisms that multiply inside living cells and can cause diseases like polio, which led to his groundbreaking discovery on the polio vaccine.

He went on to receive his M.D. in 1939 from New York University College of Medicine.

His Later Discovery of a Polio Vaccine

While still at the New York University College of Medicine, he worked with Thomas Francis Jr., on some discoveries. And in 1942, joined Thomas at the University of Michigan School of Public Health to develop the killed-virus influenza vaccine to combat the influenza virus, which was first tested for safety and effectiveness on the U.S. military, before being licensed for the general public in 1945. This sparked a new idea about vaccines. Instead of following the common scientific belief that only live, attenuated (weakened) viruses could provide immunity, he suggested that a killed virus might work just as well. However, most scientists disagreed with him.

In 1947, he left his mentor Thomas Francis Jr., to be appointed as director of the Virus Research Lab at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. A year later, he was invited to join a project funded by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFIP), which became widely known as the March of Dimes. The group was created in 1938 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had polio himself. At the time, people supported the March of Dimes by mailing their dimes to the White House to help fight a disease that struck over forty-five thousand Americans each year. With his massive help, an experiment was ready to be tested.

He first ran the experiment on monkeys, as they “were the only experimental animal that the virus would reliably infect,” and found that it yielded the desired result. Then came the dreaded moment: testing it on humans. Which he did in the year 1952. However, he didn’t exclude himself and his family from the test. He also experimented it on himself, his wife, and their children. On March 26, 1953, he went on a national radio to announce the success of the small group of human tests.

The Big Announcement

In 1954, a large-scale test was carried out in what is now considered one of the largest medical trials in history, which involved over 1.8 million children across the United States.

The following year, on 12 April, 1955, the vaccine was announced as “safe, effective, and potent.”

Shortly after the announcement, TV-journalist Edward R. Murrow asked Salk a simple but powerful question: “Who owns the patent on this vaccine?” In the 1955 interview transcript, Salk replied: “Well, the people, I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?”

That statement captured his philosophy. Salk did not pursue profits from the vaccine. In other words, he did not earn personal gain from the polio vaccine, and that allowed the vaccine to reach millions of children without the added layer of patent-driven cost or delay. The WHO records that “Salk was committed to equitable access to his vaccine, and understood that elimination efforts would not work without universal low- or no-cost vaccination.”

The choice had practical implications. The vaccine formula was shared with multiple manufacturers so that large-scale production could begin. Firms licensed to produce the vaccine included several pharmaceutical companies. The lack of a patent meant fewer legal or financial barriers to widespread manufacture and distribution. Again from the WHO “Six pharmaceutical companies were licensed to produce IPV, and Salk did not profit from sharing the formulation or production processes.”

By 1957, it was reported that annual cases of the disease dropped significantly from 58,000 to 5,600, and by 1961, there were only 161 cases reported. But would his vaccine stand for a very long time?

The Challenger

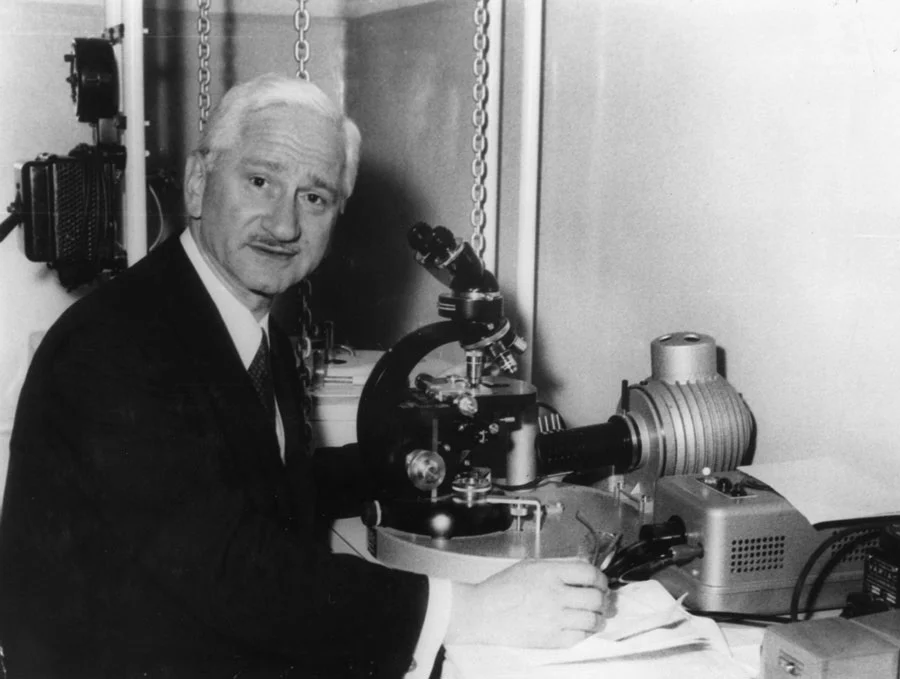

Then came Albert Sabin, a physician and microbiologist of the University of Cincinnati who had begun his research on polio in 1931, long before Jonas Salk’s vaccine was announced as safe and effective in April 1955. Himself like every other physicians who believed in the conventional way of using a live-attenuated (the virus in weakened form) argued that Salk’s vaccine would fail to provide long-term protection from polio.

Albert Sabin’s own was an oral polio vaccine (OPV), meaning it can be taken by mouth, as drops or on a sugar cube without injecting.

By 1958, experimental trials were carried out on 20,000 children in the Soviet Union, since Salk’s vaccine was still popular in the United States with many having little to no interest in testing this new kind of vaccine. The test then extended to 10 million children in 1959. With careful observations, it was announced as safe and effective and was licensed for commercial use in the U.S. on March 1961.

While Salk’s vaccine was also safe and effective, it was however, the ease of administering the oral vaccine that made Sabin’s vaccine an ideal candidate for mass vaccination campaigns, and also became the main defense against polio in the U.S. and many other parts of the world.