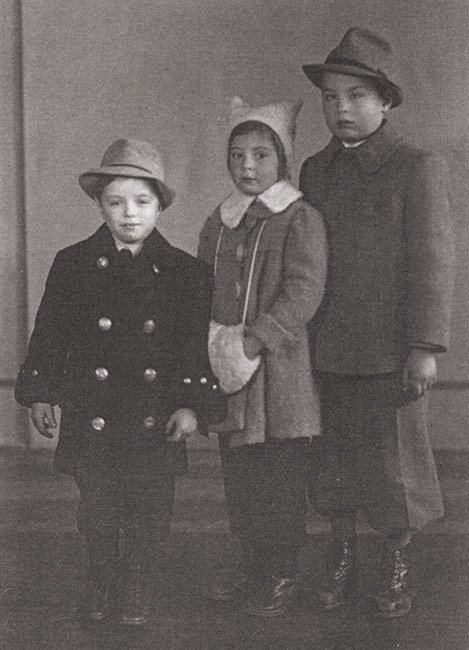

In April 1941, Dr. István (Stevan) Deneberg, a dentist, and his wife Dr. Hilda Deneberg (born Hauser), lived with their two sons, Mirko, 11, and Pavle (Paul), 8, in Subotica, northern Serbia, in the Vojvodina region near the Hungarian border — an area which remained under Hungarian control between April 1941 to March 1944.

In March 1944, Germany invaded Hungary and its territories, in an effort to prevent the Hungarian government from negotiating with the Allies. Until the German occupation, Hungarian authorities largely protected the Jews living in Budapest and other towns across the country. They regarded Subotica, known to them as Szabadka, as part of their own territory, which before the war, was a home to nearly six thousand Jews. But with the Hungarians now on their side, began rounding up Jews and deporting them in large numbers to concentration camps. It was at this moment, the family was separated. Dr. Stevan was deported to a labor camp in Bačka Topola where he could eventually face a possible death. And his wife and children?

Shortly thereafter, they and other Jews were sent to the Subotica ghetto in Paralelna Street on May 1944. It was there they remained awaiting to be deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp. However, Dr. Stevan’s brother, Janči, was determined to save them from being deported. But how could he achieve this since he was Jew himself?

Before now, Janči, had already been married to a Serbian Catholic woman, and had also become a friend to a priest, who had given him a false birth certificate identifying him as a Catholic from birth. Carrying along with him his mother’s maid, set out to smuggle them out of the camp using a cart he had already filled up with dry grasses. On arriving and getting in through by bribing the standing guard, realized it was just his nephews he could rescue. But there was still a major problem after he had successfully smuggled them out — where they would stay. He feared that if they were to stay with him at his home and the authorities learn about their disappearance, their first bet would be his place. So he knew he had to try something different.

He first turned to a Hungarian lady, a friend of his, who agreed to take the children in, but only until nightfall, as her fiancé, a police officer, was expected to return from work. Since he was running out of time to meet up to the agreed upon time, some of his friends decided to take them in for two days, to afford him the time to look for a safe place to keep them. He managed to find a non-Jew woman ready to take them in for a price, but the demanded payment was far beyond his means, leaving him with no option but to keep them with her for a few days.

With no more safe place to keep them after withdrawing them from the non-Jew lady, decided to turn to his friend, the priest who had already helped him to fake his birth certificate earlier. “Take the children to Klara Baić, a Bunjevka,” the priest told him, handing him the address to her place. However, when he arrived with the children, Klara wasn’t in Subotica. Her house was left in the care of a relative called Ester, who allowed them in after hearing about their condition. When she did returned on June 28, she was shocked to find two unknown boys in her house.

Frantic at first, she refused to let them stay because of the high risk involved in sheltering Jews, plus the high cost of living then. The boy’s uncle, however, pleaded so much with her and even offered to foot a part of the children’s feeding. Klara, a single mother herself, had a 12-year-old daughter, Margita, who had already become a friend to Mirko and Pavle (Paul). Probably sensing the fear on her daughter’s face of losing her friends, or her motherly instincts finally kicking in, no one could tell. However, what can be said was that she decided to let the children stay with her. But it was far from over.

Rumors spread that some Jews were still hiding in Subotica, and searches began immediately for anyone who had avoided deportation. Klara who had anticipated such events, with the help of Ester, prepared a place in her neighbor’s yard to safely hide them. In early September, she took her daughter and the boys to live with a relative, where they stayed until the area was liberated in October 10, 1944, by the Russians. She died in 1994, and was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem on 18 February, 2007, for her bravery.

The boys on their part were reunited with their mother, Hilda, who survived Auschwitz and returned to Subotica after the war. She recalled meeting up with her husband, Dr. Stevan once again in the Auschwitz camp, where they were again separated. When she eventually returned back home on August 4, 1945, found just the children and heard nothing more of her husband.